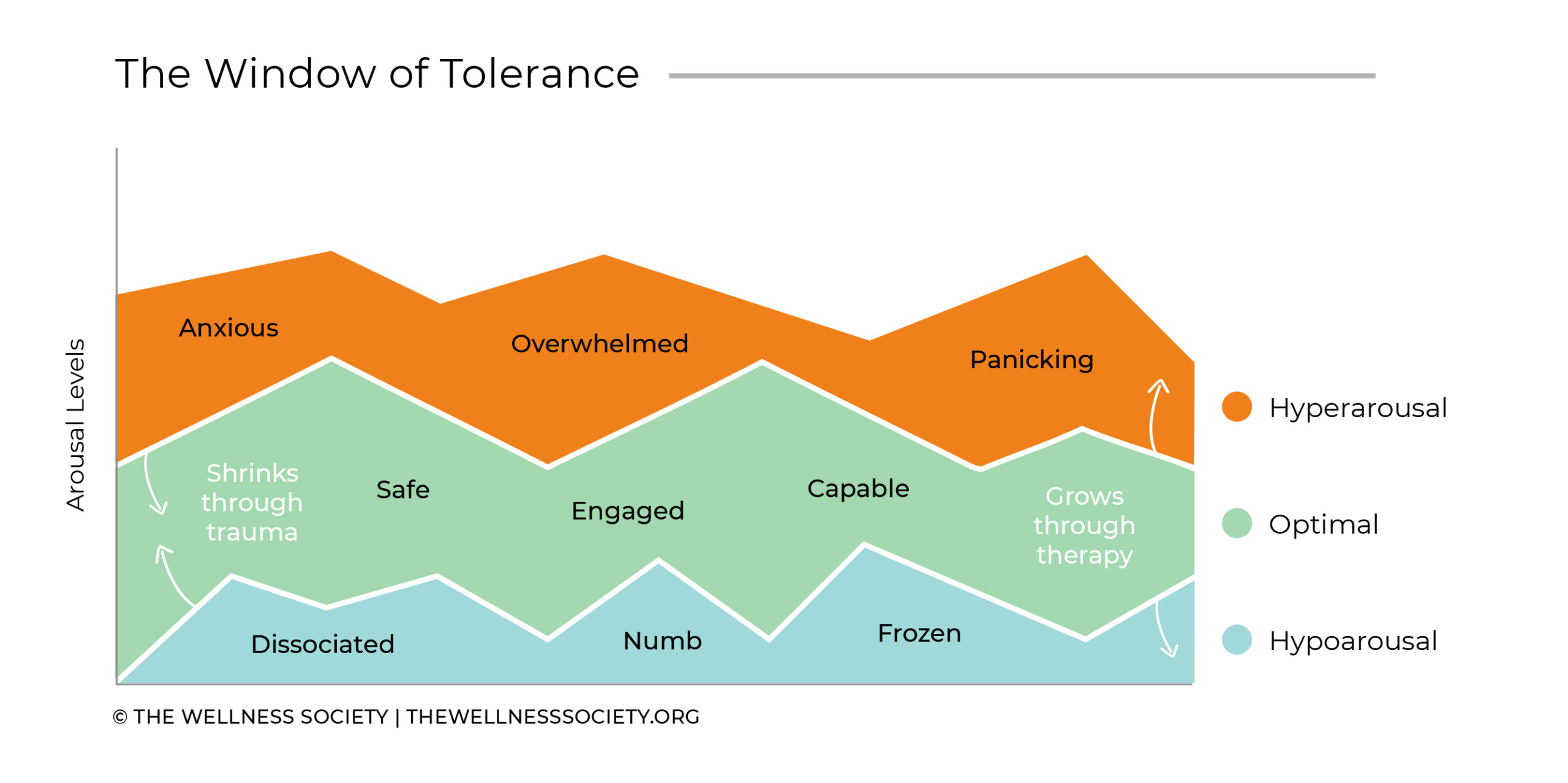

The concept of the ‘window of tolerance’ was put forward by Prof. Dan Siegl in his 1999 work The Developing Mind. It describes a middle ground of emotional functioning in which our levels of arousal are best placed for us to effectively process and thrive in our environment.

The window lies between the states of hypoarousal and hyperarousal of the nervous system. Both of these states occur when the environment is perceived as overwhelming, and our minds and bodies are primed by the threat of attack. In the former, we're shut down emotionally, disassociating from the environment. In the latter, we enter a state of extreme vigilance, and our evolutionary ‘fight, flight or freeze’ response is triggered.

In this article, we'll explore the concept of the window of tolerance in relation to working with victims of trauma. Given the pervasive nature of trauma (particularly in those seeking therapy), the effective use of the model in directing therapy has wide application.

Operating Outside of the Window of Tolerance

The effects of operating outside of one’s window of tolerance have been noted throughout history. To take just one example, soldiers fighting in World War One displayed symptoms of both hypo- and hyper-arousal.

For some soldiers returning from the front ‘shell shock’ or ‘battle fatigue’, as their condition was then termed, manifested in withdrawal, extreme lethargy and emotional numbness. Physical symptoms such as loss of vision and/or paralysis were also noted.

For others, a constant state of hyperarousal manifested in anxiety and restlessness. Slight triggers prompted extreme reactions, such as outbursts of anger or violence, as stress hormones were being produced at far higher levels than normal.

In both cases, the soldiers were unable to effectively engage with their everyday environment because they were operating outside of their window of tolerance.

The Impact of Trauma

Traumatic events often cause us to suddenly shift outside our window of tolerance.

This is a normal human response as the nature of actual events are not safe and secure. They trigger us to move into a protective zone – shutting down emotionally to avoid being overwhelmed, or speeding up to react to danger.

However, trauma can also lead to a narrowing of the window of tolerance even after the return to a safe and secure environment. In other words, the environment continues to be perceived by the sufferer of trauma as highly threatening. This is particularly acute in cases of repeated exposure to trauma, resulting in a fearful-avoidant attachment style.

We now know that there are physical costs associated with existing in a state of hypo- or hyper-arousal. Dr Bessel van der Kolk’s hugely influential work The The Body Keeps the Score provides a vivid account of the impact of trauma on our brains, minds and bodies.

Aside from the problematic symptoms of existing in a state of hypo- or hyper-arousal, operating outside the window of tolerance prevents an individual from being able to process their experience of trauma and integrate the lived experience within their sense of self. This makes living in the present difficult, if not impossible.

Re-Traumatisation Risk

Therapists are alert to the risk of re-traumatisation when working with clients who have experienced traumatic events. Ensuring that our clients are operating within their window of tolerance is vital to ensure their safe recovery as, where the window has narrowed, the risk of re-traumatisation is high.

Working With Clients to Widen the Window of Tolerance

A member of the LGBTQI+ community, let’s call him Owen, has a lifetime of experiences in which he was subject to homophobic bullying and abuse, including a serious physical assault.

It's clear from the initial assessment of Owen that his window of tolerance had been severely compromised and that his therapist will need to deploy a number of therapeutic techniques to ensure that their work together will not re-traumatise him.

Breathing Exercises and Mindfulness

Initially sessions are slow-going and only five to 10 minutes per session can be spent discussing some of Owen’s least worst experiences of homophobia. These brief patches of time where Owen was operating within his window of tolerance are punctuated with swings into a state of hyperarousal.

At this time, Owen is not able to talk about the most traumatic events of his life. As a result, his therapist is not aware he had been seriously physically assaulted.

In order to work through the periods of hyperarousal in session, the therapist uses breathing exercises and mindfulness. Owen is a keen football fan. After initial breathing exercises, the therapist introduces a football, which Owen is encouraged to hold in front of his chest with both hands. Feeling the stitching indentation on the football and tracing these with his fingertips, Owen’s happier associations allow him to return to his narrow window of tolerance where he feels safe.

Community Connection

As time moves on, Owen is able to work within his window of tolerance for longer periods, the therapist explores Owen’s internalised feelings of homophobia. As with many victims of trauma, Owen is full of self-blame.

After about 6 months of weekly counselling, Owen’s window had expanded enough for him to begin engaging with the LGBTQI+ community and he receives support and understanding from others (who all shared, to some degree, his experience of discrimination and homophonic violence).

Realising community connectedness is often a pivotal point for victims of trauma. Being amongst others with shared experiences can help to normalise one’s emotional responses and find meaning in one’s own lived experience.

Meaning Making

Owen’s final stages of therapy focus on finding a meaningful narrative which allow him to integrate his experiences, and in particular to place his attack in the past.

Seeing how he can live in the present and make new meaningful memories without being pushed into hyperarousal by his memories of the attack conclude Owen’s therapy sessions using the model of the window of tolerance. Owen’s expanded window of tolerance allow him to regain hope for the future and his curiosity for life.

Summary

The window of tolerance refers to the optimal zone of arousal where we can effectively cope with stressors and manage daily life. The goal of therapy is often to help people expand their window of tolerance, allowing them to handle a broader range of emotions and stressors without becoming overwhelmed or shutting down.Techniques such as breathing exercises and mindfulness can be used to help achieve this. By staying within the client's window of tolerance, therapists can provide support that promotes healing and empowers clients on their mental health journey.

Trauma-Informed Tools to Improve Your Mindfulness Skills

Our three-step system helps beginners as well as seasoned practitioners enhance their mindfulness skills. Explore a wide variety of methods and discover what works best for you.

About Stef

Dr Stephanie (“Stef”) Garner is a qualified counsellor and a member of the Australian Counselling Association. She specialises in working with gender, sexuality and relationship diverse clients, such as members of the LGBTQI+ community, as well as those engaged in alternative relationship models (such as consensual non-monogamy or polyamory) and kink practitioners. Stef practices person-centred therapy and has been living and working in Bangkok, Thailand since 2012. She holds a doctorate in philosophy (University of Oxford).

Find out more about her on her website, Facebook or email her at stef@unicorncare.one.